Iran’s Military Drills Prompt New Challenges for Baku

Photo By inosmi.ru

On October 1, Iran carried out a series of large-scale military drills at an unprecedented scale in the north-eastern part of the country, near the border with Azerbaijan. In response, on October 3, Azerbaijan, along with its ally Turkey, made an announcement on launching joint military exercises in Nakhchivan, the Azerbaijani exclave bordering Iran from the north. The developments of recent weeks have strained relations between Baku and Tehran. While the most recent reason for the escalation could be the increased pressure on Iranian truck drivers by Azerbaijani security forces, tense relations between Baku and Tehran have been building up for years. Today, even though Azerbaijan has been victorious in the second Nagorno-Karabakh War, it may be confronted by a new threat from the south.

Iran’s fears

The most recent cause of the escalation between Baku and Tehran appears to be the detention of two Iranian truck drivers by Azerbaijani security forces. The drivers were delivering goods to Armenia through a land route passing through small slices of Azerbaijani territory. The route is the main artery between Armenia and Iran, and Iranian trucks use it to supply Armenia and the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh as well.

The land where the drivers were detained has been internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan since the collapse of the Soviet Union, but was taken over by Armenian forces in the aftermath of the first Karabakh war between Azerbaijan and Armenia in the 1990s. Nevertheless, Baku regained control over the region in the last year’s war. Since then, Baku has taken control of the territory with a tough policy on entries into the territory via Armenia. According to Armenian media reports, Azerbaijani police checked Iranian vehicles “transporting cement to Yerevan and Stepanakert” and charged them with substantial fees. In September, Azerbaijan officially confirmed that drivers were being checked by police posts situated on “Azerbaijan’s liberated territories”.

After last year’s war, restoring transport connections, specifically a route connecting Azerbaijan to Nakhchivan and Turkey via Armenia was one of the key parts of the Russia-brokered 2020 ceasefire agreement. Since then, however, no tangible results have been achieved mainly due to never-ending tensions between Yerevan and Baku.

As Baku has attempted to ratchet up the execution of the construction of the Azerbaijan-Nakhchivan transport link, there have been some statements in Azerbaijan, suggesting that Syunik, the southern region of Armenia (known as Zangezur in Azerbaijan), which is envisioned to host the route, was an “ancestorial land of Azerbaijanis” and that they have the right to “return” there. Such comments, especially from Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, have alarmed not only Armenia but Iran as well.

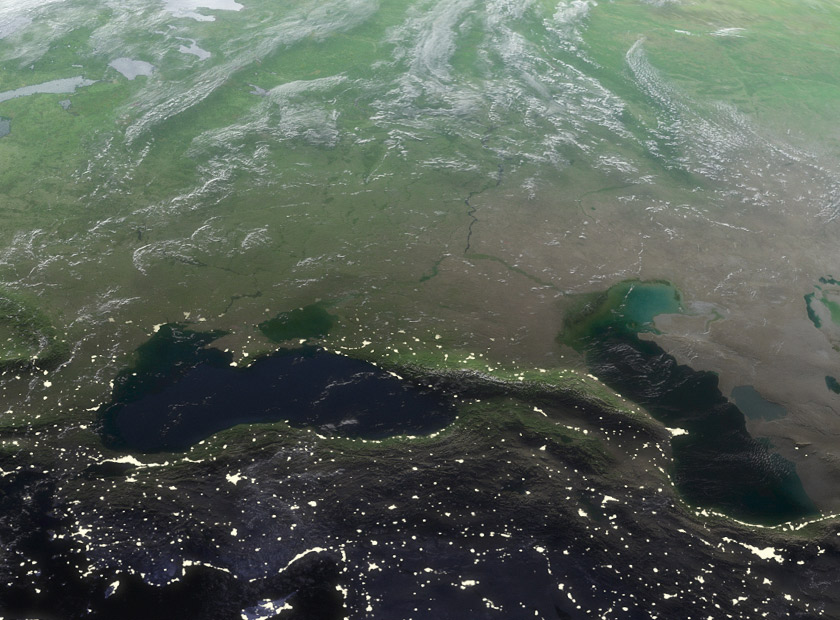

Although Iran is a supporter of Armenia’s territorial integrity and has friendly relations with Yerevan, the route connecting the two countries is essential for Tehran’s economy. Iran does not have a lot of trading partners in its neighborhood, largely owing to geopolitical ostracization from US-aligned states in the region. The land route crossing Armenia and Georgia to the further north remains the main transport gateway for Iran to the Black Sea and Europe and at the same time plays a vital role in the functioning of the North-South Corridor between Russia and Iran. The restoration of control over some parts of Nagorno-Karabakh and its surrounding districts, which were also under the occupation of Armenia, by Azerbaijan has led to Iran’s transport insecurity. To solve this issue, Tehran has been pushing the idea of building a new route to Armenia that would bypass Azerbaijan proper.

“Zionist presence”

The outcome of the second Karabakh war had a significant impact on the balance of power in the South Caucasus. The victory in the war has come as an opening for both Azerbaijan and Turkey, allied countries often referred to as “one nation with two states”. Since then, Turkey and Azerbaijan have been trying to assert their regional power through military drills, which has been the worst nightmare for Tehran. Particularly painful were the Turkish-Azerbaijani naval exercises in the Caspian Sea.

One of the major factors that have aggravated the situation is the alleged Israeli presence in Azerbaijan and Israel’s support for the country. Since its independence, Azerbaijan has developed strong strategic and economic ties with Israel, and being a secular state, it developed closer linkage with Israel, than its regional rival, Iran.

Israel views Iran as the biggest threat in the region, as it supports anti-Israeli armed groups such as Hezbollah, as well as hostile governments such as Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Azerbaijan has been purchasing military hardware from Israel, which played a pivotal role in Azerbaijan’s victory over Armenian forces last year. While Israeli-produced drones were actively involved in the Second Karabakh War, Iran has alleged that Israeli militants have been stationed in Azerbaijan. According to one leaked U.S. diplomatic document from 2009, Azerbaijan’s relations with Israel is “like an iceberg, nine-tenths … below the surface”.

This has been one of the main reasons for Iran’s security concerns. On September 30, a day before Iran began its military manoeuvres, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian had announced that Tehran would not “tolerate the presence and activities of the Zionist regime against its national security” and would opt for doing “whatever necessary in this regard”. Strikingly, the title of the Iranian military drills held on October 1 was ‘Conquerors of Khaybar’ referring to the Arabic city where Muhammad defeated the Jews in 628.

Another element of this escalation might have been the opening of a new airport in the town of Fizuli, which is located only 30 kilometres away from the Iranian border. The Fizuli airport is capable of hosting heavy transport and modern fighter jets. Given the relationship between Azerbaijan and Israel, there is some possibility that the airport may have a strategic role in the future. If Israel were to benefit from this development, it would certainly prompt concern for Iran.

By Soso Dzamukashvili