The Rehabilitation of Karabakh: Opportunities and Challenges in Establishing Peace and Reconstruction

Following last year’s 44-day Karabakh war, Azerbaijan regained control over much of the region’s territory that it had lost in the first war with Armenia in the 1990s. The loss included not only the territory per se, but produced more than half a million internally displaced people (IDPs), and fertile agricultural land as well as considerable hydropower resources were also lost. The potential economic gains for Baku after regaining control over the majority of the Karabakh region are huge, and the Azerbaijani government has already made plans to resettle the IDPs and revitalize the region’s economy and infrastructure.

Reflections on the Second Karabakh War: An Assessment of Developments One Year Later

The 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war lasted for 44-days, beginning on September 27, 2020 and ending on November 10, 2020 with the implementation of a trilateral ceasefire agreement facilitated by Russia and signed by Russian President Vladimir Putin, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev. During the 44

days of fighting, the Armenian side lost 3,788 soldiers and 224 servicemen were reported missing in action and Azerbaijan reported 2,879 soldiers killed with 28 missing in action. A number of civilian casualties were reported as well.

Download Full Report

Karabakh and Georgia’s Regional Positioning

Photo by ICR Center

Victor Kipiani

Victor Kipiani is Chairman of Geocase, a Georgian think-tank, as well as Co-founder and Senior Partner of the Tbilisi-based law firm of MKD Law.

Some Karabakh‑related Aspects of Georgia’s Regional Positioning

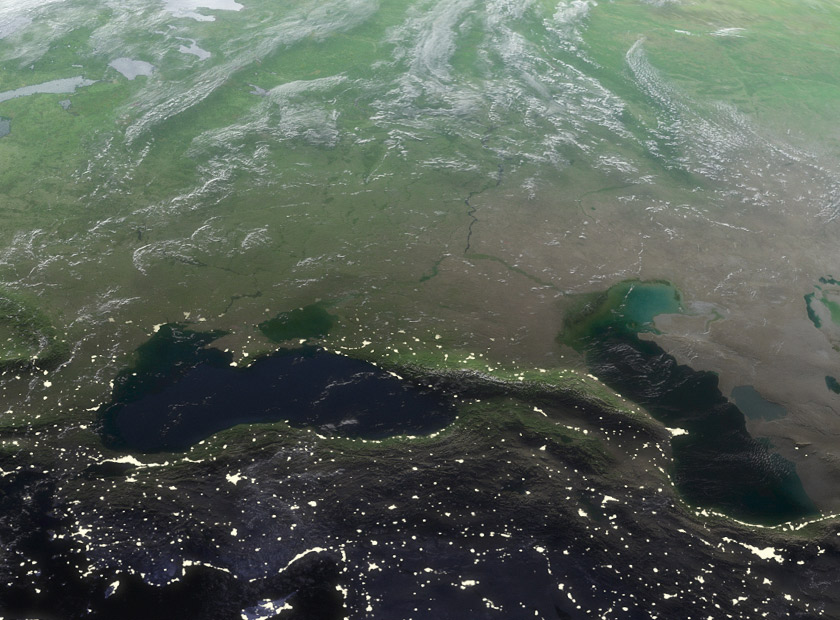

One of the geopolitical consequences of the COVID‑19 pandemic is the acceleration of a trend that predated its onset, namely the transformation of old centers of power and the appearance of new ones. This emerging new world is characterized by greater complexity, as regionalism becomes an even more important prism through which contemporary international relations can be examined. In a growing number of places across the globe, we seem to be ending up with overlapping or conflicting interests defined by the specific characteristics of different countries and how they each approach international affairs from the standpoint of their respective national agendas. In many corners of the globe, states that were formerly mere objects of world affairs are taking steps to be taken seriously as bona fide subjects of the international order, itself in the midst of a makeover—the result of which none of us can as yet reasonably predict with any degree of certainty. The South Caucasus—one of the world’s most historically and culturally diverse regions—is one of the regional nodes of the Eurasian strategic space, defined by its proximity to Russia, Central Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. The editors of Baku Dialogues have identified the South Caucasus as an integral part of the Silk Road region, an intriguing term that at the very least serves as a reminder of the fact that our part of the world belongs to a geographic continuum that has influenced and been influenced in turn by a plethora of actors located at all points of the compass, but also that we stand at the confluence of an untold number of historical processes that go back millennia.

Certainly, the South Caucasus is not simply a geographical expanse, but a critical crossroads over which the regional policies of the West, Russia, and China are at loggerheads. This is not even close to the entire picture, however. Iran and Turkey are immediate neighbors. Ukraine, Iraq and the Levantine states are quite close, as are Turkmenistan, and other Central Asian states. But so too are Romania, Bulgaria, and Greece, as are Afghanistan and Pakistan. And on it goes. All pursue their own interests, as do their respective allies, and in many cases there interests are not free of incompatibility. Indeed, it would be difficult to deny that the South Caucasus is a front or a theatre in the meta‑conflict that contraposes several normative worlds of international relations, only one of which is democratic in character. Of the three South Caucasus states, one overtly aspires to NATO and EU membership as a matter of strategic priority, by all accounts the second is almost entirely dominated by Russian priorities and interests, and the third has opted to navigate the geopolitical shoals we share as a region by pursuing what is termed a multi‑vector foreign policy.

It would be difficult to deny that the South Caucasus is a front or a theatre in the meta conflict that contraposes several normative worlds of international relations, only one of which is democratic in character.

The modern structure of relationships between the countries of the South Caucasus also has evolved over the past few years, progressing from mere bilateral relations to a more complex multi‑layered system. In this diversity, many researchers and politicians see certain historic parallels as well as the new contours of a post‑pandemic international order. For now, the Caucasian puzzle raises more questions than it provides answers. The question of the two so‑called “frozen conflicts” on Georgian territory, the unresolved complexities arising out of the Second Karabakh War’s outcome (including the quest to establish a formal peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan), and neighboring confrontations over the rearrangement of the South Caucasus model of power and the correct redistribution of interests therein are on the list of foreign policy priorities in many capitals around the world. What makes this complex regional order even more complicated is the equal lack among interested parties of sufficient interest in the resolution of these issues, the inadequate expression of such interests, and in some cases even the total absence of such interests.

The modern structure of relationships between the countries of the South Caucasus also has evolved over the past few years, progressing from mere bilateral relations to a more complex multilayered system.

Noteworthy is that even prior to the outbreak of the Second Karabakh War, the President of Georgia, Salome Zourabichvili, extended an offer for Tbilisi to serve as a peace platform for all parties to convene and meet. That offer was reiterated by our National Security Council during the war, and it still stands in its wake. In the meantime, we have continued to play our part, demonstrating the constructive relevance of Georgian soft power to the best of our ability. Here we can reproduce the 12 June 2021 words of U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken: “the U.S. welcomes the release by Azerbaijan of 15 Armenian detainees. We’re grateful to the Government of Georgia for its vital role facilitating discussions between the sides. Such steps will bring the people of the region closer to the peaceful future they deserve.” The statement did not add that the prisoners were exchanged for maps of 97,000 anti‑tank and antipersonnel mines buried in Azerbaijan’s newly‑liberated Aghdam district, although the corresponding Azerbaijani one did, of course, while also underscoring the role played by Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili. Armenia also thanked us for our successful mediation, as did various European and OSCE officials. In a significant way, Georgia’s important role in this postwar humanitarian endeavor serves to frame how we see the axis of the issue and our contemporary standing in the region more broadly.

Axis of the Issue

Georgia’s main political vectors in the South Caucasus are cooperation for peace and stability as well as maintaining good neighborly relations with both Armenia and Azerbaijan—an approach that became even more prominent during the Second Karabakh War and one that has continued in its wake.

More precisely, I refer to the statement that Georgia’s National Security Council issued near the beginning of the war—on 3 October 2020, to be precise—in which the Georgian side convincingly underlined the need to “take all necessary measures” to “stop the violence and resume dialogue” and concluded by underlining that “it is in our common interests to stop the armed confrontation and restore peace in the region as soon as possible.”

Tbilisi acted according to the conditions defined by the current reality in the region and was using the maximum of its abilities due to this reality.

On the same occasion, the National Security Council also announced that the Government of Georgia was taking specific measures in this regard: the “temporary suspension of the issuance of permits for transiting military cargo through its territory in the direction of both said countries, be it by air or land.” It also offered up Tbilisi as a neutral location for negotiations between Yerevan and Baku.

Regarding the National Security Council’s statement, one can distinguish between two principal issues. First, Georgia not only demonstrated its attitude towards the conflict but also expressed the country’s readiness to participate in the process of normalizing the situation in the region. Second, in this statement, Georgia’s government distinctly explained the importance to the country’s two largest ethnic minorities (i.e., ethnic‑Armenians and ethnic‑Azerbaijanis) of maintaining stability and order. Thus, the National Security Council’s statement and Georgia’s policy towards conflicts in general could be summed up as: Tbilisi acted according to the conditions defined by the current reality in the region and was using the maximum of its abilities due to this reality.

When talking about a possible Georgian component in various efforts to normalize the new situation in Karabakh resulting from the outcome of the Second Karabakh War, it is noteworthy that in different mass media outlets the question of the quality of Tbilisi’s coordination with Western partners has been considered more than once. On this topic, I should like to mention that any similar kind of coordination or communication undertaken by Georgia could only be defined by the reality of the current situation in the region and by Georgia’s possibilities.

However, when discussing this specific topic, it is important to clearly reiterate that Georgia’s coordination with the West over issues linked to the South Caucasus should not depend solely upon the dynamics associated with the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the wake of the Second Karabakh War. It is important to remember that the partnership between Georgia and the West originally began as early as during the second half of the 1990s when large hydrocarbon transport projects——e.g., the Baku‑Tbilisi‑Ceyhan oil pipeline (BTC), various South Caucasus gas pipelines—were initiated.

Aside from this aspect, which contributes strategically to the West’s energy diversification strategy (and will do so for decades to come), another relevant issue for further discussion is the objective evaluation of how strong Western interests and influence truly are in the South Caucasus. Accordingly, when one speaks of Tbilisi’s efforts to strengthen these interests, one should deliberately underline the fact that the efforts of our Western partners are just as (if not even more) vitally important for any kind of Western‑led cooperation or coordination in the South Caucasus.

There have been some pessimistic evaluations regarding the aforementioned new transport corridors. But when it comes to the potential weakening of existing Georgian corridors, this pessimism is to some extent exaggerated.

Transport Component

The 10 November 2020 tripartite agreement between Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia that brought the Second Karabakh War to an end— coupled with subsequent documents signed by the same three parties derived therefrom—call for new transport corridors on the territory of Azerbaijan and Armenia. Without going into too much detail regarding these projects, next I want to discuss whether or not they pose any kind of risk to Georgia’s potential for transport and transit before proceeding to the other points I wish to make. Now, it’s true that there have been some pessimistic evaluations regarding the aforementioned new transport corridors. But when it comes to the potential weakening of existing Georgian corridors, I believe that this pessimism is to some extent exaggerated. Here are five basic points that can be made.

One, the decision to go ahead with a large transport project cannot be merely the subject of geopolitical discussions at the level of “I want this and I don’t want that”—to put it in colloquial language. It is also important to remember that any project or initiative must be carried out according to a specific investment model. In other words, if a project is not based on clear and self‑sufficient financial resources, then it will be impossible to carry it out, for it might well turn into a dubious deal or a half‑completed enterprise. Without a genuine readiness to provide serious financial support, managing projects such as BTC, the various South Caucasus gas pipelines, or the Baku‑Tbilisi- Kars railway line solely according to geopolitical calculations would not have been sufficient.

Two, one must also mention the need for trust in the stability of the future operation of these corridors or projects. As a general rule of thumb, it takes several years to generate such trust, and through a series of complicated processes the project acquires its characteristic geopolitical and geo‑economic image. Nowadays, one could easily say that the so‑called “Georgian transport corridors” have already obtained the signatures they need.

Three, certain paragraphs of the tripartite agreement on the creation of new transport corridors with the participation of Azerbaijan and Armenia are quite ambiguous and unclear. For example, no considered interpretation of these paragraphs gives a clear feeling that the implementation of a specific transport project is once and for all predefined by the signatory parties of the agreement. Guaranteeing the safety of these transport links is equally important, as is the extent to which the Russian Federation can play the role of impartial guarantor in this context.

Four, we will continue to pay attention to certain aspects, including those related to transport corridors going through Georgia’s active maritime ports, which ensure the passage of goods to the Black Sea region. An intermodal system such as this, in terms of investments, is no less important since it has a direct impact on the economic component of freight transportation.

Five, one must also mention the two most important elements of the attractiveness of transit corridors passing through Georgia. The first of these is Georgia’s political system itself, which, although far from ideal, possesses indisputable advantages in terms of doing business thanks to the transparency, simplicity, and legibility of Georgian legislation.

In addition to this, what should also be taken into consideration in the big picture is the high level of Georgia’s integration with Western markets compared to its South Caucasian neighbors. And it could even be asserted that such a steady political and economic integration with Western partners is an important question not only for Georgia but would also be in the respective interest of Baku and Yerevan.

Neither of the parties to the Karabakh conflict was “hostile” towards Russia, and therefore Moscow’s actions needed to be more weighed and complex compared to other conflicts and wars in the post‑Soviet space.

A Factor of Regional Power

The next interesting question to examine is the respective roles of Russia and Turkey in the Second Karabakh War and subsequently— the Russian factor, in this case, is a very specific one. Since Russia and Armenia maintain close relations through various agreements— whereas Moscow’s links to Azerbaijan follow a more cooperation format— Russia was obliged to maintain a very delicate balance between the two warring parties.

Basically, neither of the parties to the Karabakh conflict was “hostile” towards Russia, and therefore Moscow’s actions needed to be more weighed and complex compared to other conflicts and wars in the post‑Soviet space. It was this specific factor that supposedly defined a certain number of “flexible” formulations that were included in the ceasefire agreement, as noted above.

Another defining and extremely important aspect should also be mentioned: the dinophyte or perhaps even triphylite factor of Moscow’s involvement in the conflict. What is implied here is the general background of Russia‑Turkey relations that intersect not only in the South Caucasus but in other parts around the world as well.

Despite Moscow’s tactical interests in cooperating with Ankara, Russia did its best to limit Turkey’s role in the post‑conflict period. For example, the agreement is tripartite in nature, not quadrilateral. Russia also tried hard to neutralize Turkey’s attempts to widen its role in the OSCE Minsk Group format (as well as those of Azerbaijan).

And let me now use Georgia’s point of view in order to briefly discuss what attitude Turkey can have towards this issue. Firstly, Turkey is one of Georgia’s main partners. Secondly, Ankara plays a significant role in issues of regional safety and consistently and openly supports Georgia’s NATO membership ambitions.

What is also defined in the context of this issue is the presumed specificity of Georgia‑Turkey relations with regards to limiting the spread of Russia’s influence in the South Caucasus. Here I should also mention Ankara’s desire to further deepen the country’s close partnership with Azerbaijan as well as Turkey’s practical interests in stabilizing relations with Yerevan. The subsequent treatment of Turkey as an equal to Russia in observing the terms of the tripartite agreement (to which, I reiterate, Turkey was not a signatory) at the Joint Center for Monitoring the Ceasefire in Karabakh, located in the Qiyameddinli village near Agdam, speaks to this point. On the other hand, so does the fact that Turkish troops play no operational role on the ground in what is now understood to be the Russian peacekeeping zone in Karabakh (the area not under the direct military control of Azerbaijan in the wake of the Second Karabakh War, as defined in the aforementioned trilateral agreement).

It is almost not even worth asking what benefits any format of trilateral cooperation between Baku, Tbilisi, and Yerevan would bring to the three countries of the South Caucasus.

Trilateral Format?

It is almost not even worth asking what benefits any format of trilateral cooperation between Baku, Tbilisi, and Yerevan would bring to the three countries of the South Caucasus. Besides questions of peace and safety, some sort of trilateral partnership within the framework of the emerging new world order would give the South Caucasus qualitatively different characteristics and would make the region more interesting and appealing to foreign, especially Western, investors.

Unfortunately, the reality of the current situation in the short and medium term does not give much cause for optimism. Overall, the geopolitical paradigm of the South Caucasus is mostly limited to bilateral relations between Georgia and Armenia and Georgia and Azerbaijan.

Based on that, the quality of cooperation among the South Caucasus triangle of states for the foreseeable future will be defined by the quality of cooperation between Tbilisi and Yerevan, on the one hand, and Tbilisi and Baku, on the other. At this stage, one must repeat that this is the current state of the region’s geopolitical reality—its Realpolitik, if a region can be said to have one—and that there seems to be little chance of this reality changing any time soon. These conditions underline Georgia’s most important role as a potential pillar of the South Caucasus’s overall economic space. Consequently, the results of the country’s internal reforms are becoming as important as the quality of Georgia’s integration with international civilized society.

No one can exclude that in what can be termed the “arrangement of priorities,” the South Caucasus might turn into an essential component of modern mutual compromises between Ankara and Moscow.

Issues in Perspective

Many key issues are being accumulated in the context of discussions regarding regional processes in the short to medium term. The answers to some questions are slowly taking shape with more or less focus and clarity, and some might be made the subject of hypothetical modeling—at this stage, at any rate— whilst taking existing conditions into consideration.

For example, the quality and durability of the current geopolitical cohabitation enjoyed by Russia and Turkey in the South Caucasus is questionable, particularly as the two states come into contact in other parts of the world as well. No one can exclude that in what can be termed the “arrangement of priorities,” the South Caucasus might turn into an essential component of modern mutual compromises between Ankara and Moscow.

The basic challenge of the overall task remains the role of the West in the South Caucasus and the projection of Western interests onto the regional fabric. An unequivocal answer must be found to this question at this stage, especially given the noticeable deficit of clear geopolitical Western lines with regard to the Black Sea region—one of whose natural components I believe the South Caucasus to be. The most compelling factor of the overall Western vector is the United States, whereas globally Washington’s recent zig‑zag geopolitical signature unintentionally helps to create the aforementioned problem.

Another very important issue is the overall framework of the new world order that is currently being formed. Many of us Georgians believe that there are two fundamental trends that define its basic nature: the first of these is the counterweight parameter between the United States and China as well as how this is reflected on different geopolitical geographies. Here I can refer to President Joe Biden’s recent statement effectively rejecting nation‑building (the context was Afghanistan, with the rejected concept defined as “trying to create a democratic, cohesive, and unified” country, something that has never been done over the many centuries of [its] history”), which is of course not the same as the rejection of the use of force there or anywhere else when a “vital national interest” is at stake. A few days later, at an event held at MGIMO in Moscow, the Russian foreign minister interpreted this statement, as well as one made by French president Emmanuel Macron around the same time, as being tantamount to saying “that it was time to give up on interfering in other countries’ internal affairs in order to impose Western‑style democracy on them.” He noted that if these statements “are a true reflection of their hard‑won understanding of the matter,” then “our planet will be a safer place in the future.” In my view, this interpretation is not exactly persuasive, to put it diplomatically.

The second fundamental trend that defines the basic nature of the framework of the new order that is currently being formed is, in my opinion, the novel understanding of this new world order’s multilateral characteristics as well as bringing regionalism to the fore. From this point of view, the geopolitical geography of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea—along with the South Caucasus lying in between—is being established as an important regional center of this new world order.

To complete this analysis I can indicate that the South Caucasus and the Middle East are closely linked issues, as Svante Cornell writing in a previous edition of Baku Dialogues has elaborated. Despite differences on the surface, it is a fact that a number of measurable factors are leading these two regions’ geopolitics to increasingly merge.

It is relatively simple to opt for international or overseas reliance, but much harder and trickier to define a right balance without tilting towards either complete dependency or absurd self‑determination: both options promise nothing but self‑inflicted wounds and much suffering.

Of course, the above‑mentioned questions imply several subsidiary questions and a certain depth of inquiry. I have only mentioned those basic lines of thought that will become fields for endless research by analysts over the coming years and will become routine responses for policymakers.

The Caucasian Puzzle

The fact is that the South Caucasus is once again at the center of global attention, while the modern structure of relationships between the countries of the region has evolved over the past few years from a bilateral model to a more complex multilayered system. In any case, the collapse of the Soviet Union left a legacy that the three countries of the region are still trying to overcome. Also, it is important to note that the so‑called “ethnic conflicts” of the South Caucasus are primarily related to the shifting sands of geopolitics in the region. The latter point is especially true when speaking about the conflicts in Georgia and Azerbaijan, whose reduction to the category of “ethnicity” reflects either a lack of knowledge or an attempt to distort their essence. At bottom, each is ultimately about territory and international law.

To this I wish to add that the late twentieth and early twenty‑first centuries have reverberated with major shifts to what used to be commonly referred as the liberal international order—the culmination of the development of a Modern World Order, one could say—and have borne us ever more swiftly towards an even more contemporaneous term I can call “World 2.0.” When it comes to the destiny of small nations like Georgia, the question is one of two worlds: beyond simply maintaining oneself on the map, one must become a distinctive and unique contributor to the global community, acting as a sui generis participant in world affairs on an equal and non‑discriminatory basis.

It is also worth emphasizing that it is relatively simple to opt for international or overseas reliance, but much harder and trickier to define a right balance without tilting towards either complete dependency or absurd self‑determination: both options promise nothing but self‑inflicted wounds and much suffering. Various historical examples of such blunders can illustrate the depth and complexity of the choice. Besides, it is even more worth remembering that abiding by strategic values while rationalizing reality is the hardest mission a small nation must face. Doing so is reminiscent of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1936 statement: “the test of a first‑rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” But it is precisely that first‑rate intelligence that we need—and we Georgians, as a small nation, certainly do need to retain the ability to function. The remainder of Fitzgerald’s statement is worth reproducing: “One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise. This philosophy fitted on to my early adult life, when I saw the improbable, the implausible, often the ‘impossible’ come true.

As a result of all of this, the Caucasian puzzle raises more questions than it provides answers— which is hardly surprising since the region’s importance is felt far beyond its boundaries and since the diversity of the Caucasus is truly a contributor to the grand design of Eurasian security. In addition to a general toolkit, ours is a region that also requires a very tailor‑made approach.

This article was reprinted with the explicit permission of ADA University.

Moldova Celebrates Independence While Transnistria Braces for Change

Photo By republika.md

Despite emphasizing pragmatism and openness to negotiate, newly elected Moldovan President Maia Sandu has again called for Russia to withdraw the up to 2,000 troops stationed in the Russian-backed breakaway region of Transnistria.

A pro-Western technocrat and former World Bank analyst, Sandu had avoided discussing the conflict in the run up to her July 2021 election. But in an August 23 interview with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty on the 30th anniversary of Moldova’s independence from the Soviet Union, President Sandu affirmed her commitment to negotiating the “frozen conflict on our territory” while avoiding “a destabilization of the situation.”

Estimates of the number of Russian troops in Transnistria – which has not been recognized by the United Nations or the international community – vary between 1,400 and more than 2,000. Whether tasked as peacekeepers or security for Soviet-era arms depots, the imposition of Russian troops has incited a domino effect of regional anxiety. When the Russian Federation annexed Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula in the spring of 2014, it also initiated military exercises between the Operational Group of Russian Troops in Transnistria (OGTR) and Russian Federation troops, as reported by Al Jazeera. A repeat of these exercises in Transnistria in April increased regional tension once again, leading Ukraine to bolster its State Border Guard along its border with Moldova. This represented the largest buildup of troops since Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

This saber rattling coincides with border conflicts throughout the region due to waves of new immigrants and refugees throughout Eastern Europe. Newly elected Peace And Solidarity Party deputy Rosian Vasiloi – whose Sandu-led party swept to power on an anti-corruption mandate – told EuroNews that stopping human trafficking and smuggling across the Transnistrian border will require nothing short of Moldovan authorities taking over the rebel state’s border management.

As Russia has been firmly entrenched since the 1990s, any new movements from the Moldovan side will likely be viewed as provocations threatening to upset the existing status quo. To avoid destabilization, the most effective confidence building measures would involve people-to-people communications in order to reestablish trust amongst the general population. However, due to the division between the respective societies, the conflict will likely remain ‘frozen’ until confidence building measures induce a gradual ‘thaw.’

Evaluating the Term “Displaced Persons” A Background Guide

The 1951 Refugee Convention defines a refugee as “any person who: owing to a well-founded fear or being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the

country of his nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”

Fractious Karabakh Peace Provides Washington With Opportunity in the Caucasus

Photo by Rufat Abas.

The Russian-mediated peace deal [AC1] that ended the Second Karabakh War in November between Armenia and Azerbaijan is not a calm one. It came only after three ceasefires failed, with the longest lasting one day, the second [AC2] lasting hours, the shortest barely minutes.

The peace recognized Azerbaijan’s wartime territorial gains. Azerbaijan retook half of Nagorno-Karabakh (including the strategic and cultural city of Shusha) and the territories Armenia occupied since 1994. Russia achieved its long-standing goal of deploying troops in Nagorno-Karabakh, even if it shares an observation post with a Turkish mission. But Putin’s ceasefire focused on getting those Russian troops into Karabakh, and left a host of other pressing issues untouched. These issues present opportunities for the United States to bolster its presence in a region that has emerged as a linchpin for global geopolitical security.

A major problem effecting the peace is the contamination of Nagorno-Karabakh and the recovered territories of landmines and other unexploded ordinance that are the legacies of decades of ongoing conflict. Azerbaijan has estimated mine clearance operations will take upwards of a decade, and Baku has asked Yerevan to turn over maps of minefields to assist with clearing the land. Believing the minefields[AC3] are necessary to the defense of Armenia and what remains of Armenian-held Nagorno-Karabakh, the Armenian government has so far refused to turn over these maps.

Then there are the Armenian prisoners of war (POWs) held by Azerbaijan. So far Baku has returned 61 Armenian POWs (58 in February, three in May), though the European Court of Human Rights says that Azerbaijan continues to hold 188 Armenian POWs. Baku has only confirmed detaining 72 Armenians, 62 of whom were captured in the Azerbaijani province of Hadrut in December, a month after the official end of hostilities. Because of the time of their capture, Azerbaijan calls them terrorists, not POWs, and is refusing to return them.

And culture is another sticking point to peace. For Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh, referred to as the Republic of Artsakh by Armenians, is the birthplace of the Armenian nation. For Azerbaijan, the city of Shusha in Nagorno-Karabakh is the cultural heart of the Azerbaijani people. Following Armenia’s conquest of Nagorno-Karabakh 1994, over 800,000 Azerbaijanis fled Armenia and Karabakh (while over 250,000 Armenians fled Azerbaijan[AC4] ). Armenia destroyed several mosques in Yerevan and Nagorno-Karabakh following the Azerbaijani exodus in 1994; the surviving mosques have been renovated[AC5] in a ‘Persian style’ to erase Azerbaijan’s connection to Karabakh.

But Azerbaijan is not free of sin. In May, photos emerged of the removal of the Armenian Ghazanchetsots Cathedral’s dome in Shusha, though Baku said this was to repair damage caused by falling shells. The creation of a ‘Military Trophies Park’ in Baku following the Second Karabakh War is another example of the inflammatory rhetoric (coming from both sides) sustaining the conflict. Opening with a display of Armenian helmets taken from the bodies of Armenian soldiers, the park shows visitors wax models of Armenian soldiers bearing strange and frightening countenances. In an interview, the statues’ creators confirmed their goal was to “create the most freakish depictions” of Armenians possible. Such displays are inimical to peace between Armenians and Azerbaijanis.

Washington should take advantage of these unresolved issues and set up a trilateral working group between Baku, Washington, and Yerevan; should Baku and Yerevan make meaningful steps towards peace and reconciliation, then Washington would invite the sides to Camp David to formalize the peace. The first step could be accomplished by having Azerbaijan release all Armenian detainees listed by the ECHR, while Yerevan would exchange the relevant minefield maps to all parties involved in mine clearance operations.

Regarding the cultural issues, the United States should offer the services of the Smithsonian Institution in the preservation and renovation of religious and cultural landmarks in the region. The Smithsonian has extensive experience in such work and has operated in hazardous areas, having sent teams to restore artifacts in Iraq and Syria destroyed by Islamic State and is notably impartial. Washington should also condition future aid to both Baku and Yerevan on efforts to clamp down on anti-Armenian and anti-Azerbaijani/Turkish rhetoric coming from official channels. A first step would be at least taking down the offensive statues in the Military Trophies Park, if not the dismantling of the Park itself, which is hardly conducive to establishing peaceful relations.

Moscow has no intention of resolving these issues, which provides space in the region for Washington. If President Biden wants to combat Russian aggression and show that the United States remains a credible international force, then he should start in Karabakh.

The Mafia’s Wars

The 1990s saw the emergence of the Russian mafia as a powerful force in Russian political and social life. Under President Putin’s patronage, the mafia has become an extension of the Russian state. Join us as ICR Center Chair Christopher Chambers talks with journalist Olga Lautman on the influence of the criminal underworld in the frozen conflicts plaguing the former Soviet Union.

Azerbaijan Field Visit After the Second Karabakh War

Representatives of the International Conflict Resolution Center traveled to Baku, Azerbaijan to gather information about the history of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict; the ongoing issues and relations between Armenia, Azerbaijan, third countries, and the international community; and the reconstruction efforts that will take place in the territories reclaimed by Azerbaijan during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war. The delegates of the organization met with representatives of both governmental and non-governmental organizations in the capital city of Baku. Members of the International Conflict Resolution Center met with the leaders of the Azerbaijani Community of Nagorno-Karabakh, the Vice-Chairman of the Russian Community of Azerbaijan, the leadership of the Center of Analysis of International Relations (AIR Center), officials from the Azerbaijani Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Hikmet Hajiyev, the Assistant to the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan and Head of the Foreign Policy Affairs Department of the Presidential Administration. For the second part of the field visit, the representatives traveled to regions in the western parts of Azerbaijan to meet with regional officials. Regional officials in the cities of Ganja and Tartar coordinated visits for the representatives to observe damages inflicted during the war. These territories were located within the internationally-recognized borders of the Republic of Azerbaijan, located far away from the conflict zone. The representatives of the

International Conflict Resolution Center concluded their visit by visiting Aghdam with a military escort, a city that was decimated by Armenian forces during the first Nagorno-Karabakh war between 1988 and 1994.

Download Full Report

New Russia Policy

The Donbas Crisis has shown that the U.S. and European policy on Russia is in desperate need of review. Join the International Conflict Resolution Center’s Chair Professor Chirstopher Chambers as he talks with Dr. Stephen Blank, a Senior Fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute’s Eurasia Program, to learn what a new and effective Russia policy for the Biden Administration would look like.

The Ukrainian Crisis

The Ukrainian Crisis: A Conversation with Generals Benjamin Hodges and Michael Repass

Join ICR Center’s Professor Christopher Chambers as he sits down with Lieutenant General (retired) Benjamin Hodges and Major General (retired) Michael Repass to discuss the latest troubling developments of the Ukrainian conflict.

March 30 – April 5

The Caucasus Headlines

China Donates 100,000 Doses of Coronavirus Vaccine to Georgia

China will donate 100,000 doses of the Sinovac vaccine to Georgia in April according to Amiran Gamkrelidze of Georgia’s National Center for Disease Control. Georgia received 100,000 doses from China last week, and the country has plans to purchase additional doses. Sinovac has been approved for use in more than 30 countries, including Hungary, Turkey, and Mexico. Gamkrelidze noted that Georgia will overcome the pandemic if 60 percent of the population receives vaccinations, however, recent surveys indicate that many Georgians do not plan to get vaccinated.

Trial of Former President Kocharyan Adjourned

On March 30, the trial of the former President of Armenia, Robert Kocharyan, was adjourned by Judge Anna Danibekyan of the Yerevan Court of General Jurisdiction because the prosecutors were not present for the trial. Kocharyan is currently accused of violating Article 300.1 of the Penal Code, overthrowing the constitutional order. The court will convene again on April 6 to consider whether or not to terminate criminal prosecution against Kocharyan. The decision will be announced at 5:45pm Yerevan time.

Azerbaijan Announces New Plans for Agricultural Production

In a recent video conference between Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and Zaur Mikayilov, the recently appointed Chairman of the Amelioration and Water Resources Open Joint Stock Company, Aliyev announced new measures for improving the nation’s food security. Aliyev noted that Azerbaijan has a diversity of climate and this should be used to the country’s advantage in accelerating development for providing food for the growing population. The President also noted that with proper management, Azerbaijan will be able to increase its export potential, contributing to the growth of the non-oil sector.

Sources: Agenda.ge, Armenpress.am, Report.az

Eastern Europe Headlines

Biden Calls Zelensky Amidst Russian Troop Buildup

U.S. President Joseph Biden called Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky for the first time on April 2. The call comes as Russia deploys approximately 15,000 troops for military exercises along the Russian-Ukraine border. President Biden pledged ‘unwavering’ support for Ukraine in his call with the Ukrainian President.

Ukraine Cracks Down on Smuggling

On April 2, the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine met and placed personal sanctions on the top ten smugglers in the country. This is the first time Ukraine has used personal sanctions against smugglers.

Ukraine to Join NATO in Iraq

Colonel Andriy Pavelko announced that Ukraine will contribute troops to the ongoing NATO mission in Iraq as well as to the NATO Operation Sea Lion in the Mediterranean. This comes as Ukraine is working to further cooperate with the Western military alliance.

Sources: rferl.org, ft.com, unian.info

Abkhazia/South Ossetia

Georgian Citizen Released from South Ossetia Prison

On April 1, Georgia’s State Security Service reported that Ramaz Begheluri, a Georgian citizen, had been released from pre-trial custody in Georgia’s occupied Tskhinvali region. Begheluri was detained on February 2 by Russian forces near the Gugutiantkari village in the Gori region. Begheluri’s arrest was discussed within the Geneva International Discussions as well as the Ergneti Incident Prevention and Response Mechanism.

3,000 Ethnic Georgians Detained for Crossing Abkhaz-Georgian Border in First Quarter of 2021

In the first three months of 2021, approximately 3,000 ethnic Georgian residents of the Gali district were detained for alleged illegal crossings into Georgia proper. Starting in February 2020, Abkhaz authorities closed the Enguri crossing point. Abkhaz officials have allowed humanitarian corridors several times during the pandemic, but a full reopening is not expected anytime soon.

Abkhaz, Russian Officials Meet in Moscow

Daur Kove, the Foreign Minister of the regime controlling Abkhazia, traveled to Moscow on April 2 to meet with Mikhail Bogdanov, who serves as the Special Representative of Russia for the Middle East and Africa as well as the Deputy Foreign Minister. The parties discussed Abkhazia’s status internationally and methods of improving Russian-Abkhazian foreign policy interaction. Russia continues to indicate that it will invest in strengthening Abkhazia’s presence internationally.

Sources: civil.ge, Apsnypress

Crimea

Presidential Spokesperson Indicates Planning for Crimean Platform Continue

According to a statement by Iuliia Mendel, the Spokesperson for the President of Ukraine, officials are actively discussing the format and programming for the Crimea Platform summit, which is planned for August 23. The Crimean Platform has been created to improve the international response and recognition to the occupation of Crimea by Russian forces. It is also designed to draw attention to human rights violations.

Russia Accused of Launching Conscription Initiative in Crimea

As Russia has built up its forces in Donetsk and Luhansk, the European Union has accused Russia of launching a conscription initiative in Crimea to draft residents of the occupied region in the Russian Armed Forces. The E.U. has stated that this military conscription effort is another violation of international humanitarian law.

Sources: ukrinform.net, RFE/RL

Donetsk/Luhansk

Conflict in Eastern Ukraine Experiences Escalation

In the past week, the conflict in Eastern Ukraine has escalated sharply. In Donetsk, Russian-backed separatists killed four Ukrainian soldiers and wounded another during a buildup of Russian forces on the border. Open-source intelligence shows that Russia is actively moving troops and military equipment into the region.

Further Ceasefire Violations Reported in Occupied Ukrainian Territories

Russian-backed rebel forces breached the ceasefire agreement 21 times on April 2. Twenty of the attacks were against Ukrainian military forces, and the other attack was against civilian infrastructure. The violations were largely comprised of machine gun fire and artillery.

Sources: ukrinform.net, The New York Times

Nagorno-Karabakh

Iskander Missiles Discovered During Demining Operation in Shusha

During a demining operation in Shusha, the Azerbaijan National Agency for Mine Action (ANAMA) discovered the remains of Russian-made Iskander-M missiles, which are capable of carrying nuclear warheads. The Armenian military allegedly only has Iskander-E missiles, which have a shorter range, in its arsenal. Analysts suggest that the Iskander-M missiles were fired from Russia’s 102nd military base in Gyumri, Armenia.

Azerbaijan Accuses Armenia of Supplying Incorrect Maps of Landmines

On the International Day for Mine Awareness and Mine Action, Assistant to the President Hikmet Hajiyev issued a statement alleging that Armenia has yet to provide the correct maps of landmines in the liberated territories. According to Hajiyev, the National Agency for Mine Action (ANAMA) initiated a demining effort using maps supplied by Armenia, but nothing was found, indicating that ANAMA had been misled. Demining efforts are one of the main tasks in restoring the liberated territories.

Armenia-Azerbaijan State Border Remains Stable

According to the Defense Ministry of the Republic of Armenia, a stable operational situation with no incidents has been maintained along the Armenia-Azerbaijan line of contact. Additionally, no incidents were reported in the Vorotan-Davit Bek section of the Goris-Kapan road, which is monitored by the Armenian National Security Services.

Sources: Oxu.az, Armenpress.am

Transnistria

Transnistrian President Meets with Senior Kremlin Aide

Vadim Krasnoselsky, the President of the Transnistrian breakaway state, met with Dmitry Kozak, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s Deputy Chief of Staff of the Presidential Executive Office. The two reportedly discussed the continuance of ties between Russia and the breakaway territory as well as the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

Transnistrian President Discusses Issue of Negotiations with Moldova with Russian Official

Transnistrian President Vadim Krasnoselsky met with Andrei Rudenko, the Deputy Foreign Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. Krasnoselsky thanked Russia for supporting Transnistria in fields including efforts to counter the coronavirus pandemic. Krasnoselsky informed Rudenko of the status of communication with Moldova, which he described as having ‘alarming tendencies associated with the further degradation of the dialogue.’

Sources: Novosti Pridnestrovya

Moldova’s Frozen Conflict

Understanding the Politics of Moldova’s Frozen Conflict: An Interview with Executive Director of the Institute for European Policies and Reforms and Board Member of the Institute of Strategic Initiatives Iulian Groza.

In this interview, ICR Center Chair Professor Christopher Chambers sits down with Iulian Groza, the Executive Director of the Institute for European Policies and Reforms and Board Member of the Institute of Strategic Initiatives. Learn about the history of the frozen conflict in Moldova and its effects on the country’s politics and relations with its neighbors.

March 23 – March 29

The Caucasus Headlines

Georgian Ruling and Opposition Parties Prepare for EU-Mediated Talks

Leading up to the EU-mediated talks between Georgian Dream and its rival political parties, Georgian Dream stated that it is willing to continue talks with even the most ‘destructive’ parts of the opposition. A party representative stated that Georgian Dream has already enacted compromising steps to help resolve the political crisis, and the party expects the opposition members to negotiate an agreement that benefits the entire country.

Azerbaijani, Armenian, Russian Foreign Ministers to Meet in Moscow

On March 26, spokeswoman for the Russian Foreign Ministry Maria Zakharova stated that Azerbaijani Foreign Minister Jeyhun Bayramov will meet with Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov. Lavrov is also scheduled to meet with Armenia’s Foreign Minister Ara Ayvazyan. The parties will meet on April 2 as part of a CIS Council of Foreign Ministers meeting. A meeting between the Foreign Ministers of Azerbaijan and Armenia has not yet been confirmed.

Armenian Lawmakers Lift Martial Law Ahead of Elections

Armenian lawmakers have voted to lift martial law, imposed at the beginning of a 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, as it prepares for early parliamentary elections in June. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has said his parliamentary bloc plans to pass amendments that would switch the electoral system to a fully proportional one before snap parliamentary elections scheduled for June.

Sources: Agenda.ge, Report.az, RFE/RL

Eastern Europe Headlines

Kremlin Arrests Father of Navalny Ally on Corruption Charges

Ivan Zhdanov, a Navalny associate and director of the Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, has reported that his father has been detained by state authorities on March 29. Mr. Zhdanov has said that the arrest was meant to put pressure on him. His father, Yury Zhdanov, was arrested for recommending that the town of Rostov-on-Don help subsidize an apartment for a local woman, who apparently had previously received housing allocations. Ivan Zhdanov himself was arrested and served a 15-day jail term in 2019 for joining an unsanctioned rally to protest the Moscow municipal elections.

Kremlin Spokesperson Says Talks Between Ukrainian President Volodymr Zelensky and Russian President Vladimir Putin are not Scheduled

Kremlin Spokesperson, Dmitry Peskov, told the Russian TASS news agency on Monday that there are no plans for a phone call between Presidents Putin and Zelensky, though it could be arranged. This announcement was made shortly after Oleksiy Arestovych, an adviser to the head of the President’s Office, said that such a conversation was being planned. President Zelensky himself said he was looking to set up a conversation with President Putin to complement the ongoing Normandy Format negotiations. The Normandy Format, comprising France, Germany, Russia, and Ukraine, was set up to bring a negotiated end to the Donbas Conflict.

Belarusian Authorities Arrest 200, Cordon Belarusian Capital

Belarusian police arrested 200 people on March 27, and cordoned off streets in Minsk, the country’s capital. This came after calls for renewed mass protests against the results of the latest Belarusian presidential election which resulted in Belarusian President Aleksander Lukashenko winning a sixth term. The election was seen by many as fraudulent, which has resulted in on-and-off mass protests throughout the country.

Sources: RFE/RL, Unian.info

Abkhazia/South Ossetia

UNHRC Adopts New Resolution on Georgia’s Occupied Territories

On March 24, the United Nations Human Rights Council adopted a new resolution highlighting the deteriorating human rights situation in Russian-occupied Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The resolution — titled Cooperation with Georgia — stresses the concern of the UNHRC in the continued process of borderization and use of artificial barriers to create division between Georgia and its own territories. The UNHRC also expressed concern over the continued discrimination against ethnic Georgians.

Abkhazia, Russia Strengthen Ties Through Cultural Cooperation Plan

Ministers of Culture of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Abkhazia Olga Lyubimova and Gudisa Agrba signed an agreement on March 25 to increase cooperation in the field of culture during 2021. The two parties discussed the limitations in the promotion of cultural activities in light of the coronavirus pandemic, but Russia will assist Abkhazia in holding in-person and online events through educational institutes this year with the purpose of ‘further strengthening cultural and humanitarian interaction.’

Sources: Civil.ge, Apsynpress.info

Crimea

Ukrainian Journalist Confesses to Spying Charges, Torture Suspected

On a March 18 televised interview, the Ukrainian journalist Vladislav Yesypenko publicly confessed to spying on behalf of Ukraine. Mr. Yespyenko is a freelance contributor to the website Crimea.Realities, which is a regional news outlet for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Ukrainian service. The head of the organization Reporters Without Borders’ Eastern Europe and Central Asia Desk, Jeanne Cavelier, said on March 26 that he was concerned that Mr. Yesypenko was subjected to ‘psychological and physical pressure.’ Mr. Yesypenko has also been charged with ‘making firearms,’ a sentence punishable by up to six years in prison.

Sources: RFE/RL

Donetsk/Luhansk

Ceasefire Broken Again Over Weekend, Casualties Reported

On March 26, rebel forces in the Donbas broke the ceasefire, with six casualties (four Ukrainian soldiers killed, two injured) from shelling. An additional ten ceasefire violations, which included shelling, mining, and one skirmish, occurred on March 28, although no Ukrainian casualties were reported.

Ukrainian Minister Estimates 25-30 Years to Demine the Donbas

Oleksiy Reznikov, Ukrainian Minister for Reintegration of Temporarily Occupied Territories and Deputy Prime Minister, announced on the TV Channel Dom that landmine clearance in the Donbas will take an estimated 25-30 years. The minister based this estimate on the nature of the war and the experience of Croatia following its secession from Yugoslavia. The minister refrained from estimating the amount of money required to demine the territory, as such estimates could only be made after returning the rebel territory to Kyiv’s oversight.

Sources: Unian.info

Nagorno-Karabakh

Parliament of Nagorno-Karabakh Gives Russian Official Status

The parliament of Nagorno-Karabakh approved a proposal to make Russian the ethnic Armenian-populated region’s second official language, along with Armenian. The bill says that giving the Russian language an official status would deepen Nagorno-Karabakh’s history of “cultural, military, and economic links” with Russia. Nagorno-Karabakh is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan, where Azerbaijani is the only official language of the country.

Azerbaijan’s President Signs Decree on Urban Development in Liberated Territories

Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev signed a decree on the topic of governance and urban planning in the recently liberated territories of Azerbaijan. Under the new decree, the State Committee for Urban Planning and Architecture will be responsible for determining land use, the issuance of construction permits, and transferring any category of land from one category to another.

Sources: Armenpress.am, Report.az

Transnistria

Transnistrian Authorities Appeal Russia for Vaccine Shipment

On March 24, the Supreme Council of the de facto Transnistrian government sent a resolution to Russian President Vladimir Putin to provide Covid-19 relief. The resolution asked the Russian president to send COVID-19 vaccines to save the lives of Russian citizens and Russian compatriots living in the rebel region. This request comes as Transnistria, like most of Europe, is being hit by a third wave of the virus.

Sources: MFA of Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic