The Limits of Russia’s “Separatist Empire”

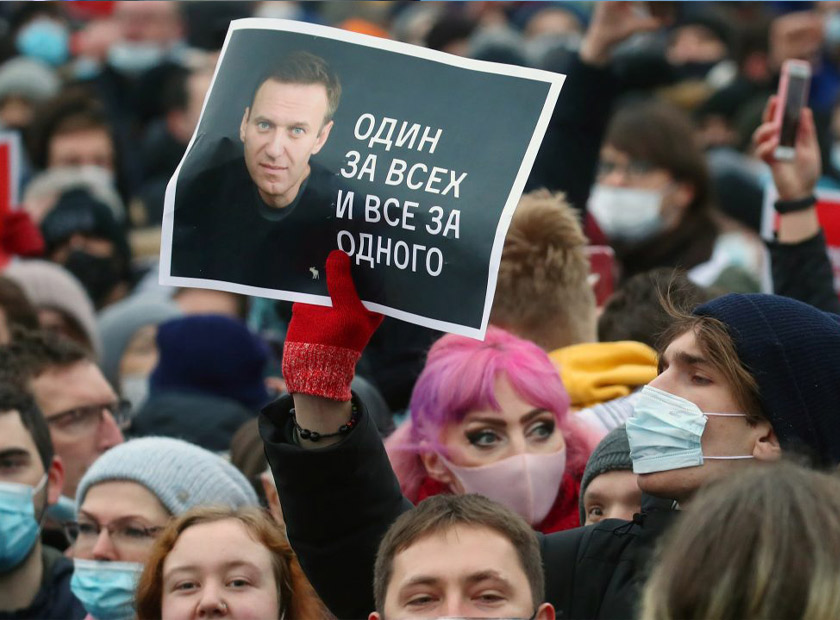

Photo By 123.ru

An important part of Russia’s grand strategy since the 1990s has been the use of separatist conflicts across the post-Soviet space for geopolitical aims. Moscow’s competition with the West over the borderlands – i.e., the regions that adjoin Russia from the west and south – has involved keeping Moldova, Ukraine and the South Caucasus from joining the West through deliberate stoking of separatist conflicts. This policy has been successful so far, as the EU and NATO have refrained from extending membership to Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. However, over the past several years Russia has started to face long-term problems: financing the separatist territories; attaining wider recognition for the separatist regions; inability to reverse the pro-Western course of Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine; and the failure to produce a long-term political or economic development vision for the unrecognized territories.

Russia’s policy towards the conflicts in the post-Soviet space has been conditioned by various factors ranging from Moscow’s relations with the West, Turkey and Iran, pure military calculations, as well as ups and downs in bilateral ties with specific neighboring countries. Though it has been hard to see the emergence of a veritable Russian strategy in the 1990s and early 2000s towards the territorial conflicts, by 2020 (as evidenced by the second Nagorno-Karabakh war results) it could be argued with some certainty that a purposeful use and subsequent management of separatist conflict zones across the post-Soviet space has turned into an important part of Russia’s grand strategy toward the Eurasian landmass.

The emergence of the strategy is also closely related to the ongoing geopolitical competitition Russia has with the West over the borderlands – i.e., the regions that border on Russia from the west and south. The rivalry is manifested in the expansion of Western institutions such as the Eastern Partnership and NATO into Eastern Europe and as a countermeasure, Russian efforts to build the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) with the aim to engulf what once constituted the Soviet territory. Therefore, maintaining the buffer states around Russia has been a cornerstone of the Kremlin’s foreign policy against the West’s eastward projection of military and economic influence. The emergence of the Russian strategy toward the separatist conflicts has also been conditioned by the arising constraints as an effective countermeasure against the neighboring states’ westward geopolitical inclinations. The Russian political elite knew that because of the countries’ low economic attractiveness, the South Caucasus states would inevitably turn to Europe and the US. The same was likely to occur with Moldova and Ukraine on Russia’s western frontier, as their geographical proximity to and historical interconnections with the West render them especially willing to pursue pro-Western foreign policy.

To prevent Western economic and military penetration and the pro-Western foreign policy vector in the neighboring states, the Kremlin has on many cases deliberately fomented various separatist conflicts. This policy has proved successful so far. The EU and NATO refrained from extending membership to Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova because Russian military presence in those countries serves as the biggest obstacle for the West’s institutional expansion.

However, Russia now faces a major problem: it has so far failed to produce a long-term vision for the separatist regions. Creating a unified economic space with the separatist territories is not an option as usually little economic benefit is expected. Even if in some cases benefits still could be harnessed, the territories’ poor infrastructure prevents active Russian involvement. Additionally, local political elites are often sensitive to Russian domination. For instance, Abkhazia has for decades resisted Russian businesses from buying the local lands. Moscow understands that more financing has to be dedicated to the regions, whose populations could otherwise turn increasingly disenchanted with hopes they pinned on Russia. Indeed, the system is difficult to navigate for Russia since while in the first years following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia had to manage breakaway conflicts only in small and poor Georgia and Moldova, Moscow’s responsibilities increased significantly by late 2020 with separatist Donbas and now Nagorno-Karabakh conflict added to its strategy. One could also add Syria to the list. The latter’s inclusion might be surprising, but considering the level of Russian influence there and the stripping away of many of Damascus’s international contacts, the war-torn country is essentially now fully dependent on Russia security-wise.

This means that at a time when economic problems resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, Western sanctions, and the lack of reforms are looming large on the Russian home front, Moscow has to pour yet more money into multiple separatist actors spread across the former Soviet space, as well as Syria. Moscow’s broader strategy of managing separatist conflicts is therefore under increasing financial stress. For instance, recently it was announed that Russia plans to spend a whopping $12 billion in the next 3 years for separatist territories in Ukraine.

It is more and more difficult for the Kremlin to maneuver across so many diverse conflicts simultaneously. At times, actors in the conflict zones try to play their own game independently from Moscow and the latter has to closely monitor any deviations lest it harms the Kremlin’s strategic calculus. This often happened in Abkhazia when, for instance, in early 2020 Raul Khadjimba resigned not without Russian interference or in Donbas, where occasional infighting as in 2015 and 2018 among rebel groups takes place.

Apart from internal differences, the geographic dispersal of those conflicts also creates difficulties for Russia’s projection of power. Geopolitical trends indicate that Russia’s long-term strategy to stop Western expansion in the former Soviet space is losing its rigor. While it is true that Moscow for the moment stopped its neighbors from joining the EU and NATO, its gamble that those separatist regions would undermine the pro-Western resolve of Georgia and Ukraine has largely failed.

Apart from a failure to preclude pro-Western sentiments among the neighboring states, economic components also indicate Moscow has been less successful. Western economic expansion via the Eastern Partnership and other programs is proving to be more efficient.

Nor can the Russian leadership entice states around the world to recognize the independence of breakaway entities. For instance, in the case of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, only Syria, Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Nauru have extended recognition.

Russia lacks any long-term economic vision for the breakaway territories. Dire economic straits have inevitably caused populations to flee toward abundant medical, trade, and educational possibilities other countries provide. Usually these are territories from which the separatist forces initially tried to break away. Abkhazians try to use benefits provided by Tbilisi, so do the Ossetians, which once again highlights the fact that the Kremlin has failed to transform those entities into secure and economically stable lands. Crime levels as well as high-level corruption and active black markets have been on an upward trajectory, which undermines the effectiveness of financial largesse Moscow has to provide on a regular basis.

Thus a long term perspective for Russia’s “separatist empire” is not promising. Moscow is outspending the benefits it potentially can reap from poor and insecure separatist regions. Its military presence in those lands with the latest example of the dispatch of peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh highlights weaknesses in Moscow’s foreign policy – dependence on the military element in formulating the foreign policy is becoming palpable.